Hey! Remember that one particularly scary thing?

Hey! Remember that one particularly scary thing?

You know… That terrifying tale you read or heard as a kid. That creepy commercial that came on late one night. That bit of “extreme” cinema you watched on a dare. That urban legend about the vanishing hook-handed hitchhiker who wore a beehive wig full of spiders?

Yeah, that one.

You saw or read or heard it once, long enough for it to sear a itself into your brain, where it laid in wait in the back of your head till bedtime when—covered with sharp teeth, matted fur, suppurating flesh, or rippling cilia—it jumped out and said, “Hey! How’s it going? Mind if I watch you sleep? Like, forever?” Whether youthful Kindertrauma or a flaming bucket of nightmare fuel you stupidly poured over your head as an adult, some fictional fears just stick with you.

In the spirit of Halloween season, I put out a call to several Chicago writers, performers, and zinesters to share the stories, comics, films, and other things that scared them most.

“Pleasant SCREAMS, kiddies! Heeeeeheeheeheeheehee!!!”

Happy Halloween! Dan Kelly/Third Coast Review Lit Editor

Go Ask Alice was first published in 1971. It was billed as the “found diaries” of a supposedly real girl who drove her insecurities about sexual attraction to other girls as well as her general teenage malaise and fear of disappointing her parents into a full-blown pill addiction and life as a homeless sex worker. We now know that the book was written by Beatrice Sparks, a Mormon youth counselor (who went on to publish other “found works” like Annie’s Baby: The Diary of Anonymous, a Pregnant Teenager), but when I discovered a battered paperback version of Alice at the public library—with its cover photo of a half-lit spooky face—at age eleven, I freaked out, read it, acknowledged and appreciated the underlined passages involving making out and detailing Anonymous’ first LSD trip, and then saw the book on my nightstand under dim light…and freaked out some more.

Go Ask Alice was first published in 1971. It was billed as the “found diaries” of a supposedly real girl who drove her insecurities about sexual attraction to other girls as well as her general teenage malaise and fear of disappointing her parents into a full-blown pill addiction and life as a homeless sex worker. We now know that the book was written by Beatrice Sparks, a Mormon youth counselor (who went on to publish other “found works” like Annie’s Baby: The Diary of Anonymous, a Pregnant Teenager), but when I discovered a battered paperback version of Alice at the public library—with its cover photo of a half-lit spooky face—at age eleven, I freaked out, read it, acknowledged and appreciated the underlined passages involving making out and detailing Anonymous’ first LSD trip, and then saw the book on my nightstand under dim light…and freaked out some more.

I was raised Catholic, not Mormon, but guilt and shame are not scarcity economies. Honestly the writing was terrible and the drug use didn’t strike me as scandalous as the back cover advertised, but that girl’s eyes were looking at me—SHE’S LOOKING AT ME and I couldn’t look away and I hope she does fricking run away from home already because I can’t stand her LOOKING AT ME anymore.

I’m sitting in a dark room typing this right now and want to get up and turn all the lights on because I’m still thinking about that goddamned book cover.

Salem Collo-Julin is a writer and performer from Chicago who works for the Chicago Reader. https://linktr.ee/hollohulo

One of the scariest books I remember is one I’ve never read. I was the type of kid who’d sneak out of her room in the middle of the night to find a book to read. In an attempt at stealth I would turn on the absolute minimum amount of light to peruse our family bookshelves. It was in those dim shadows that I first caught sight of I Have No Mouth and I Must Scream by Harlan Ellison, and it was horrifying.

One of the scariest books I remember is one I’ve never read. I was the type of kid who’d sneak out of her room in the middle of the night to find a book to read. In an attempt at stealth I would turn on the absolute minimum amount of light to peruse our family bookshelves. It was in those dim shadows that I first caught sight of I Have No Mouth and I Must Scream by Harlan Ellison, and it was horrifying.

The cover of my parents’ edition featured a bulbous face with yellow eyes and one ear that flared out like the horn of a phonograph. As the title suggested, there was no mouth, just a lumpy void between the nose and chin. I flipped over the hideous thing, but it was too late. That grotesque visage replayed on the inside of my eyelids long after I returned to bed. And it didn’t happen only once. Despite my intention to avoid it, I remember repeatedly stumbling upon that beastly tome. Each time the image disturbed my thoughts for hours after.

I recently searched up that particular version of the cover. I was surprised not to find it very scary at all. The illustration is similar in style to Hieronymus Bosch. Strange, certainly, but nothing to cause nightmares. Perhaps it’s finally time to read the book, but if I do, I will probably choose a copy with one of the alternate covers.

Kim Z. Dale is a Chicago-based writer of plays, essays, and short fiction. Examples of her work and updates about current projects can be found at kimzdale.com.

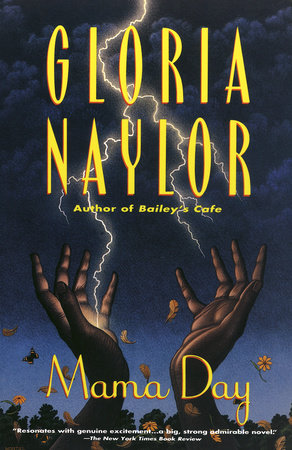

I first read it on a hot, muggy August weekend many years ago, almost all in one sitting. As I reached the book's climax, set during the beginnings of a hurricane, a huge storm rumbled in from the west, embodying in nature what I was picturing in my head. I kept reading, safe in my spot, right through the storm, as its build-up, thunderous release, and aftermath eerily mirrored the events on the page.

Was it magic manifested in the world? Did Naylor weave a spell into her novel, or was it just a coincidence? Hard to say for sure, but I will tell you this: I re-read Mama Day a few years ago, and when I reached the climactic chapter, a storm started brewing, right on cue. Maybe the same will happen for you.

Andrew Huff is the cohost of the monthly live lit series Tuesday Funk and host of 20x2 Chicago.

I was a fearful kid. Much scared me, mostly things I saw on television—horror film trailers, monster movies, and, for some odd reason, experimental films seen by accident on PBS' deeply weird Image Union show ("Bob", the mascot/drawing in those opening credits unnerved me too). But the first piece of written fiction that terrified me was a short story called—spoiler ahead—“The Thing in the Cellar”.

I was a fearful kid. Much scared me, mostly things I saw on television—horror film trailers, monster movies, and, for some odd reason, experimental films seen by accident on PBS' deeply weird Image Union show ("Bob", the mascot/drawing in those opening credits unnerved me too). But the first piece of written fiction that terrified me was a short story called—spoiler ahead—“The Thing in the Cellar”.

I didn’t read it in a book or magazine. Someone in my homeroom passed around a typewritten stack of eight pages. I recall the ink being purplish, so it might have been a mimeograph rather than a photocopy. I took my turn with it that night and returned it the next day. For a very long time sleep wouldn’t come, though I never let that on to my friends.

The plot is simple. From infancy, a young boy named Tommy is terrified of his cellar. A door to the downstairs stands in the kitchen, the single room in the house where toddler Tommy isn’t a perfectly happy little fellow. When the door is left open, he screams bloody murder until mom or pop closes and locks it. He then takes the extra measure of stuffing the cracks in the doorframe with rags and worshipping the lock with kisses. Childhood binding magic.

Tommy grows. His parents employ old-time parenting techniques to cure him: “thrashing”, sending him to bed supperless, and whatnot, but nothing helps. At age five they take him to the family doctor. The boy’s in perfect health, but his basement fear is brought up. Privately, Tommy tells the doctor there’s something down there, something bad, but when pressed to describe it, he reveals that he doesn’t know what it is. He just knows that an IT that’s entirely unrelated to Stephen King sits down there. Waiting.

Showing all the compassion of a 1930s child healthcare professional, the doc suggests Tommy’s parents nail the door open and leave Tommy alone in the kitchen for an hour to realize his fears are groundless.

Hazard a guess at where this is going.

Uttering only a brief yelp, Tommy is quickly and mysteriously no more. To use a technical term, it freaked out my shit.

Years passed, and I grew braver, becoming a horror-obsessed adult. I discovered the work of H.P. Lovecraft, Ray Bradbury, Shirley Jackson, Ramsey Campbell, and many others, but the memory of that story returned to me. I tried to track it down, mis-remembering the title as “The Thing in the Basement”, but after a time I wondered if it was a false memory—something I invented during a long-ago nightmare. Then the Internet happened, and I did a Yahoo! Or AltaVista search. Turns out, it did exist.

“The Thing in the Cellar”, written by Dr. David H. Keller in 1932, displays the usual reliable tropes: a helpless, frightened child victim whom nobody believes; a subterranean place radiating evil; useless goddamned authority figures; and a hideous, terrifying thing no one ever sees. No wonder it hit me dead center in my reptile brain, inspiring a deep distrust of my basement for much of 1978. As I recall, I could only escape our “cellar” if I ascended the steps two at a time. I slipped once and panicked, but recovered and made it out alive. Did I look back? No! Are you crazy?

“The Thing in the Cellar”, written by Dr. David H. Keller in 1932, displays the usual reliable tropes: a helpless, frightened child victim whom nobody believes; a subterranean place radiating evil; useless goddamned authority figures; and a hideous, terrifying thing no one ever sees. No wonder it hit me dead center in my reptile brain, inspiring a deep distrust of my basement for much of 1978. As I recall, I could only escape our “cellar” if I ascended the steps two at a time. I slipped once and panicked, but recovered and made it out alive. Did I look back? No! Are you crazy?

One line from the conclusion stuck with me:

Trembling, he examined all that was left of little Tommy.

We know the result of the cellar thing’s attack on Tommy—presumably a moment of joyous triumph, finally having the only being aware of its existence in its power—but we don’t know its extent. “Torn.” “Mutilated.” “All that was left.” are other terms Keller employed. Perhaps you’re picturing a few well-placed, deep scratches. Not me. My stupid, scared child brain made it worse, imagining Tommy converted into inedible ropa vieja.

Rereading “The Thing in the Cellar” today I see that Keller was only a passable writer. Stylistically, the story is dated and clunky. The characterization of the parents as slack-jawed, working-class yokels bugs me. Keller fears contractions, and the sentences lack flow. From start to finish reading it is like walking through a field of tall grass, and stumbling on hidden rocks. As an aside, it turns out Keller wasn’t just a hack, he was a ultraconservative, racist, and misogynistic one, which of course meant he was never lonely among many of his fellow sci-fi writers in those days.

And yet…

I didn’t know Shinola about good writing back then. I just concentrated on plot, and the plot for “The Thing in the Cellar” is scary as hell for a kid because it’s fill-in-the-blank. When you’re a child, you spend most of your time filling in blanks, often with the wrong info. Coming across Keller’s “The Thing in the Cellar” then was like encountering a psychopathic Mad Libs that took me forever to recover from.

Dan Kelly is the Lit editor for Third Coast Review. Visit him @mrdankelly or listen to his podcast.

El Largo Tren Oscuro (The Long Dark Train)

Sam Hiti’s El Largo Tren Oscuro is a slim, long comic—not long in terms of page count, but long like a landscape. I didn’t notice the shape of the book the first time I read it. I don’t think I noticed the title, either: the letters show up as shadows in light that streams from a skull, a beacon held by a pale woman wearing a long, funereal veil. The title is also printed on the spine, but I didn’t notice that either. It’s not the kind of book where the obvious details stand out: instead, they create a story that sucks you in with its beauty and horror, leaving you entranced and unsettled. The comic’s horizontal stretch is a subtle, perfect fit for the story within: a train full of damned passengers going somewhere terrible and inevitable. The train chugs along, the coal smoke rises, and we humans, made monstrous by all manner of sin and frailty, are along for the ride.

Sam Hiti’s El Largo Tren Oscuro is a slim, long comic—not long in terms of page count, but long like a landscape. I didn’t notice the shape of the book the first time I read it. I don’t think I noticed the title, either: the letters show up as shadows in light that streams from a skull, a beacon held by a pale woman wearing a long, funereal veil. The title is also printed on the spine, but I didn’t notice that either. It’s not the kind of book where the obvious details stand out: instead, they create a story that sucks you in with its beauty and horror, leaving you entranced and unsettled. The comic’s horizontal stretch is a subtle, perfect fit for the story within: a train full of damned passengers going somewhere terrible and inevitable. The train chugs along, the coal smoke rises, and we humans, made monstrous by all manner of sin and frailty, are along for the ride.

It’s a slow and hazy journey. Gradually, the nature of the passengers is revealed. There are suitcases full of maggots. There are mouthfuls of maggots. Maggots everywhere, on everyone, tumbling out of mouths and other orifices, and sometimes joined by snakes and other biologies. The fanged conductor rips the tickets of the slothful, gluttonous, and arrogant, and it all seems so ordinary and terrible. My gut cramps every time I return to the beautifully rendered mini-morality plays—it feels familiar in a way that smarts and lingers. But I keep coming back to those pages. I know I’m going to get on that train.

Rosamund Lannin reads and writes in Chicago. You can find her on the Internet most places @rosamund or co-hosting lady live lit show Miss Spoken this Wednesday, October 30. The theme is Ghost Stories.

Cosmically Triggered

Cosmically Triggered

What the hell is going on? I’m expecting more of the trippy, hippie philosophy of the Illuminatus! Trilogy, but Robert Anton Wilson’s Cosmic Trigger seems to be saying that if I seek shamanic enlightenment, I’m going to be abducted by UFOs and pass through Chapel Perilous’ long dark teatime of the soul. My beliefs are just neurological grids that fail to accept that I will never know why it sometimes rains frogs. Too much interest in sex, drugs, and Aleister Crowley alerts mammalian politicians who want to seal up the doors of perception. Paranoia starts to creep in, but the skeptic that lives inside my head wants to report it to the Holy Guardian Angel Higher Intelligence from Cosmic Central that orbits Sirius

Once you start to look for weird shit, you begin to notice it everywhere.

Joe Mason can't do anything without being quirky. He hosts Shameless Karaoke part-time, plays theremin in the White City Rippers, sings in the a cappella Blue Ribbon Glee Club and wrote about Chicago history for the Chicago Reader and steampunkchicago.com.

Joyful obsession over anything horror-related fueled the bulk of my 1970s childhood—especially if the ostensibly eerie object at hand seemed particularly chintzy or preposterous.

Joyful obsession over anything horror-related fueled the bulk of my 1970s childhood—especially if the ostensibly eerie object at hand seemed particularly chintzy or preposterous.

As a result, I scoured TV Guide for airings of Billy the Kid vs. Dracula, carried around a newspaper ad for The Incredible Melting Man, and I memorized both the spoken word and sound effects elements of Disney’s Thrilling, Chilling Sounds of the Haunted House LP.

Of course, I also read books voraciously. Still, these passions decidedly did not meet at the crossroads of one of the decade’s most potent and prolific portable entertainment forms: the mass-market paperback horror novel. The covers were simply too terrifying.

Two images leap screamingly to mind: the plastic-masked Catholic girl holding a bloody knife on Communion by Frank Lauria and the spooky-eyed boy on the front of Lupe by Gene Thompson, a cover made worse by the fact that it was a cut-out—you opened it up and saw he was in a coffin.

Two images leap screamingly to mind: the plastic-masked Catholic girl holding a bloody knife on Communion by Frank Lauria and the spooky-eyed boy on the front of Lupe by Gene Thompson, a cover made worse by the fact that it was a cut-out—you opened it up and saw he was in a coffin.

All horror paperbacks froze me with fear in the ’70s, but those two cover kids really rattled me because—by dint of Roman Apostolic faith and/or bugged-out baby-blues—they could have been me. Scary stuff. Still.

Mike McPadden is the author of, among other things, Teen Movie Hell: A Crucible of Coming of Age Comedies From Animal House to Zapped!

One of the few things in life that has truly rattled me to my core was the movie Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer. I saw it at the Music Box Theater in the very early 90s, with Third Coast Review editor Dan Kelly and another friend, Darrin. I’d never really been bothered by scary movies. Not that this is a traditionally “scary movie” by any means, but it was both unsettling and terrifying on a level I still have a hard time explaining to myself or anyone else.

One of the few things in life that has truly rattled me to my core was the movie Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer. I saw it at the Music Box Theater in the very early 90s, with Third Coast Review editor Dan Kelly and another friend, Darrin. I’d never really been bothered by scary movies. Not that this is a traditionally “scary movie” by any means, but it was both unsettling and terrifying on a level I still have a hard time explaining to myself or anyone else.

Part of the horror is the way it begins: we see a series of murdered women, bodies yet to be discovered, and faintly in the background we hear the sounds of their respective murders. Nothing about this movie is going to be easy. Another part of it is the time and place: mid-80s Chicago. The location was so visually recognizable, it made everything exponentially more real to me. The sound design is both murky (lots of eerie whooshing noises) and jarringly crisp at times (the snap of a neck, or the squish of blood), and both techniques are deployed for maximum horror.

The final scene of the movie is what really broke me. When a heavy suitcase is unceremoniously dumped at the side of the road we know who is inside it, and I just started sobbing uncontrollably. I remember walking out of the theater to Dan’s car, and neither he nor Darrin knew what to do with me and my extreme reaction to this. I didn’t really understand it myself. It's not like serial killers were a new idea to me, but right at that moment, seeing someone so easily dispatched and tossed aside like trash was unbearable.

This experience also kept me from being invited to see Silence of the Lambs with my friends when it came out. I thought they were just being jerks by going without me, but they were afraid I was going to freak out again. I’ve seen that movie a hundred times and it’s creepy as fuck but it never made me cry.

I’ve been tempted to watch Henry again over the years, but I never did until now, when I decided I would write about it for this. I was afraid I would react in the same way and didn’t want to re-traumatize myself, but I was equally afraid I would feel nothing, and think “What was wrong with me?” But it was still as horrifying as I remember it, and I still cried at the end.

Kathy Moseley works hard so her cat can have a better life.

As a grown-ass adult, I draw the line at owning one or two cats. I already have enough things dependent upon me for sustenance as it is. As a little girl, though, I was an insufferably obnoxious ailurophile. If the neighbor cat had a litter of new kitties, I begged to see them pleeeease with all the Brando-esque drama of Stanley Kowalski hollering “STELLA!” Of course, when I grew up I wanted to be a veterinarian, and live with ALL THE CATS. In the meantime, three of them roamed freely among the herd in my multi-species household. My childhood favorite was a chub of a tuxedo cat with excellent temperament, for he was willing to sleep at the foot of my bed every night even after a fair amount of “OKAY KITTY BE THE BABY! BE THE BABY!”-type play from his zealous mistress.

As a grown-ass adult, I draw the line at owning one or two cats. I already have enough things dependent upon me for sustenance as it is. As a little girl, though, I was an insufferably obnoxious ailurophile. If the neighbor cat had a litter of new kitties, I begged to see them pleeeease with all the Brando-esque drama of Stanley Kowalski hollering “STELLA!” Of course, when I grew up I wanted to be a veterinarian, and live with ALL THE CATS. In the meantime, three of them roamed freely among the herd in my multi-species household. My childhood favorite was a chub of a tuxedo cat with excellent temperament, for he was willing to sleep at the foot of my bed every night even after a fair amount of “OKAY KITTY BE THE BABY! BE THE BABY!”-type play from his zealous mistress.

In or around fifth grade, one of my elementary school teachers introduced our class to the stories of Edgar Allan Poe. Dork that I was, I took it upon myself to read more of Poe’s short works. While I found most to be terrifically chilling in their own way, I remember the standout scary story being “The Black Cat”. In my defense, any youngster who isn’t disturbed by the tale of a drunkard mistreating his beloved pets needs a one-way ticket to the school psychologist, pronto. The idea that hanging a CAT was a thing that adults could DO, deepened my suspicion of grownups.

Every babysitter, relative, or mail carrier who drew away from my tuxedo cat’s affectionate head butting became questionable. Oh, I’m sure they could have just been allergic, or maybe didn’t want the cat hair on their clothes. Still, how was I to trust them? Even my own father became a suspect, with his dislike of my tuxedo cat, and its tendency to curl up on his lap specifically during the Sunday football broadcast. I wondered whether his protracted trips to the bathroom during half-time were just a cover for axe-sharpening! (It turns out he just had a case of undiagnosed irritable-bowel syndrome. Silly me!)

I did take comfort, however, from one notion put into my head by the story: should I ever be dismembered with an axe and have my corpse walled up in a basement, my faithful tuxedo friend would surely avenge my death.

Or, at least, sell me out for a plate of tuna.

Jackie’s 25-year-plus repertoire of “rampant dynamicism” includes poetry, spoken word, and original monologues in and around Chicago. Find out more here.

I posture as being braver than I am. I blame it on some combination of being the youngest child, chronically tall for my age, and a Leo. So it shames me to admit my spooky threshold is so low I am still quite haunted by a book cover.

I posture as being braver than I am. I blame it on some combination of being the youngest child, chronically tall for my age, and a Leo. So it shames me to admit my spooky threshold is so low I am still quite haunted by a book cover.

My older sister had the book. It sat on her shelves, a dark spot in a sea of the colorful Boxcar and Babysitters paperbacks she used to read aloud to me growing up. I was chapter-book age, thumbing through her stacks for something to borrow, the first time I saw it, saw him--that disembodied skull, pipe clenched in a toothy grin, his eye trained on whoever dared pull that black spine from the shelf. I have never read a single story from Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark in any lighting condition, because I could never get past its cover.

My sister never let me borrow clothes or CDs, but we shared a mutual disdain for dog-earing pages, so she trusted me with her books. Even so, I wasn’t allowed in her room without her. This emaciated semi-skull still sporting last night’s clown make-up seemed like an adequate punishment. I don’t know why it affected me so much. I’m not afraid of clowns and I find skeletons silly and fun. But from that day on, whenever I scanned her shelves, I tried to ignore that book. Which, of course, meant it was all I could think about—dreaming up my own terrifying stories and context for the illustration on the cover. One time I remember seeing that spine staring at me from a bookshelf in the basement, I was convinced it was following me (it didn’t help that I was a little afraid of the basement too).

Just the other week, my sister called to ask if I had her copy of Scary Stories. She wanted to read it in advance of the TV adaptation. I told her I was confident that I did not. I’ve been thinking about that cover again ever since.

Natalie Younger is one of those actor/writer/comedian types and, therefore, is legally obligated to also have a podcast. Natalie-younger.com